All Saints Episcopal Church

All Saints’ Episcopal Church “93 Years of Episcopal Faith in West Plains”

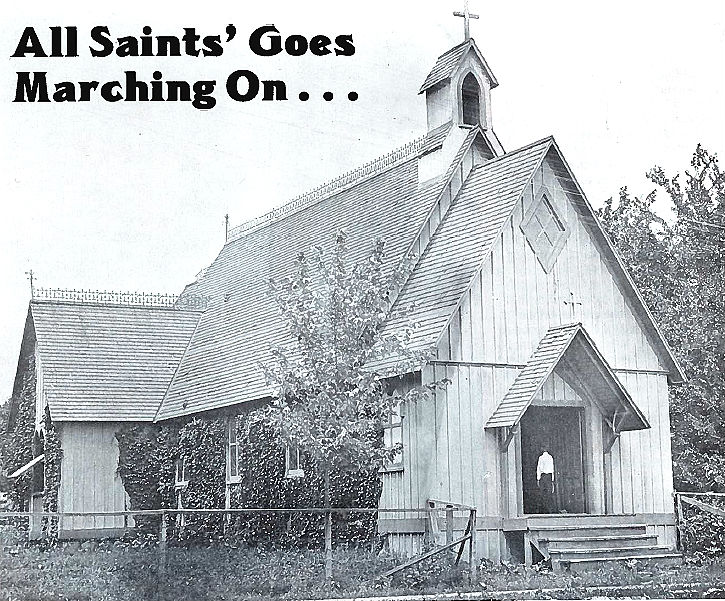

To most townspeople, the little All Saints’ Episcopal Church on Curry Street is a picturesque landmark. The quaint bell tower, the bright red doors and the white vertical siding are familiar to all who pass by.

It is interesting that, while many other historic churches have given way to larger, more modern structures, very little outside or inside All Saints’, from the altar to the stained glass windows, has changed since the cornerstone was laid in 1888. We are told this is because Episcopalians, more than most other denominations, find great meaning in a physical setting that has deep and familiar roots.

For example, when the vestry (the church’s governing lay body) recently discussed ways to conserve heat, a suggestion for lowering the ceiling was entertained only long enough for them to visualize – in anguish – the venerable beams and natural woodwork overhead that would be hidden from view.

The real story of All Saints’ is, of course, the life of its congregation – the small band of loyal parishioners who have carried on services there through the ups and downs of many generations. For that story we have turned to an insider, the wife of the parish priest.

But we find that her story of All Saints’ people, the particular liturgy they follow, and even the language that distinguishes them, cannot be separated from the church building itself.

“The Little Church Around the Corner”The history of All Saints’ is the history of a people struggling to survive and persevere, in the same way that the Old Testament is the history of a people surviving in an alien land and trying to preserve its particular faith.

There have been times when the church was filled with the Holy Spirit and did God’s bidding, and other times when, through lack of a leader or for other reasons, the congregation slipped into the Slough of Despond and members fell away.

One of the more difficult periods was around the end of World War II. Father Roy H. Fairchild had passed away several years before, and somehow the energetic leadership he had brought to All Saints’ could not be regenerated in the short tenure of several missionary priests who followed him. This period also saw the deaths of several “old guard” church members. Most of the younger men were serving in the military far from West Plains.

During those bleak years, the women and the few men who were either too young or too old for the war gathered faithfully for services led by young Joe Aid, Jr. in whatmust have seemed stubborn devotion in the face of adversity. Attendance records of that period show congregations of a dozen or so people on most Sunday mornings. According to the Episcopal way of doing things, sermons had to be sent from Kansas City (since at that time laymen weren’t allowed to write sermons) and often were inappropriate. In any case, they had a “canned” sound to them. There was, of course, no Holy Communion, except on the rare occasions when a priest visited.

Faced with similar difficulties, most other churches would have disbanded, the remaining members seeking temporary homes among other denominations. Nevertheless, the group that held together under Aid carried on the work of survival until after the war and a priest could be found to come to West Plains.

As in the Old Testament, there have also been instances when a particular person has arisen from the church’s midst to become a leader, and these persons are noted throughout All Saints’ history for their unique and oftentimes magnificent contributions.

The example comes to mind of W.W. Mantz, who was superintendent of the Sunday school for 40 years. He was also a member of the vestry and was one of the principal financial supporters of the church. We are told, “he missed almost no services and performed every kind of task for the church, no matter how humble or how difficult.”

When Mantz died in 1945, Bishop Spencer came to West Plains to conduct the funeral. This showed the mutual respect the two must have had for each other, since it is unusual for a bishop to conduct a layman’s funeral, particularly during wartime when travel couldn’t have been easy.

These contrasts in the life of the congregation over the past 93 years once led a faithful member to remark to a prospective clergyman, “An Episcopalian in the Ozarks is a strange breed of cat.”

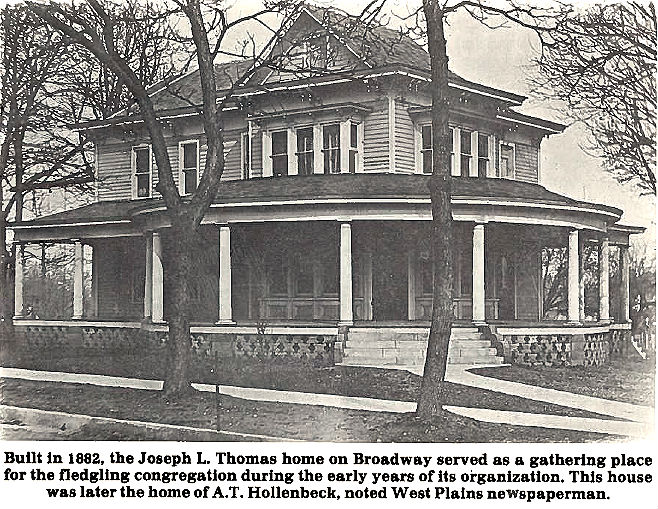

There’s an old joke among Episcopalians that the church didn’t gain a stronghold in West Plains because, while Methodists and Baptists went pioneering and evangelizing on horseback, Episcopalians waited until the railroads were built. There’s just a bit of truth in that joke, particularly in regard to All Saints’. The railroad came to West Plains in 1883, and with it came a banker, Joseph Lyle Thomas, his wife Elizabeth, and their three daughters, Lavinia, Sibyl and Anita. Thomas was one of the original subscribers to the stock in the West Plains Bank. He served as cashier there during its first year and was secretary of the board of directors for four years.

The Thomases also came armed with their beloved Episcopal Book of Common Prayer and to them goes credit for establishing the Episcopal in West Plains. They are also the first of the All Saints’ leaders whose spirit, fervor and Christian witness were unstinting.

Thomas read Morning and Evening Prayer in the library of the family home at 403 Broadway (the house that was later the home of Arch T. Hollenbeck) for two years before Father Thomas B. Lawson visited West Plains on Easter Sunday and officiated at the first Episcopal Eucharist.

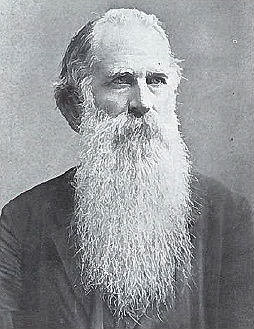

Lawson, a rather awesome looking man with a long, flowing, was an Episcopal mission priest based in Lamar, Missouri. While in West Plains, he went door to door, calling on people and entreating them to become Episcopalians.

The hall Mrs. Thomas had rented for the Easter service burned down before the day arrived. However, the first Holy Communion of the fledging congregation was held on schedule when she was able to rent the Cumberland Presbyterian Church building. The congregation on that first Sunday, we’re told, numbered five – more than likely the five Thomases.

Some of the early struggles of the Church were described in a 1938 letter from the three Thomas sisters when All Saints’ celebrated its 50th anniversary:

“Before the church was built we were wanderers and dependent upon the hospitality of the various churches in town and our ability to secure the services of a priest. “During those years of wandering, it was possible for us to have only occasional services, often at night. The town had no electricity then, so we had to pick our way over rough, uncertain roads to Evening Prayer by the light of a lantern. The prayer books and hymnals were trundled in a wheelbarrow to our temporary shelter. Sometimes the entire congregation was collected in the ‘omnibus’, probably the most imposing horse-drawn vehicle in town, which was pressed into service for weddings and funerals, as well as for the daily meeting of trains.”

Music was also important to the Thomas family. Before the church was built, they would haul the organ from their home to whatever building had been rented for the service.

In the fall of 1885, the Rt. Reverend Charles Franklin Robertson, bishop of the diocese, made his only visit to West Plains and confirmed five people. At this time, All Saints’ was “baptized” and official named. According to the Thomas sisters, “Bishop Robertson organized the mission and at our dinner table turned to Mother and said, ‘It is for you to name the baby.’ Her answer was, ‘All Saints’,’ for she loved best that the festival which commemorates the union of the church with the saints in Paradise.”

A year later, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas donated the land for the church building, and the cornerstone was laid in September, 1888. (The church was built on the site of and earlier city cemetery, and although the remains were removed to Oak Lawn Cemetery, little sunken spots still appear in the yard of the rectory as the earth settles from those early diggings.)

The conservative Ozark trait of not buying until you can pay has prevailed at All Saints’ since the beginning. The church was out of debt almost as soon as it was built. (Later, when the rectory was built in 1914 and the parish hall was built in 1957, they too were out of debt almost immediately.).

According to a 1938 church history by Mrs. Lillian B. Mantz, “Everything about the little church speaks of the devotion of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas. They are responsible for the beauty and correctness of the building plans and furnishings. The organ, the altar cross and vases and one of the lecturn Bibles are all memorials to them.”

When All Saints’ was completed, one of the first “appointments” was a Hook & Hastings tracker-type organ. Mrs. Thomas was the organist for many years and the choir was soon one of the finest in town. It included Charles Humphrey, who later became a concert singer in St. Louis.

That choir formed by Mrs. Thomas may have also been responsible for the church’s first romance, since E.J. Green and Maggie Stowers both in it. Their marriage was a short time later, in 1893, is recorded as the first in the church. Also, sadly the deaths of their two children, in 1893 and 1895, were the occasions of the first funerals in the church.

Romance in the choir loft must have caught on quickly, since the second wedding in the church, also in 1893, was that of Mary E. Mantz to Will Marsh, while Mary was church organist.

Another tradition was humorously dubbed the “Exalted Order of Organ Pumpers” or the G.O.F.P.O.P (Guild of Former Pipe Organ Pumpers). It included every small boy in church for at least two generations, until the organ bellows was motorized in the 1930s. It was rather dull work, apparently, for several exalted members would slip out the back door of the church to frolic in the sunshine, invariably slipping back in too late to pump up enough air for the next hymn. Even now, Joe Aid, Jr.’s initials can be found carved on the inside of the cubbyhole where the pumpers sat.

A present member of All Saints’ who has been a faithful communicant for more than 35 years says the spirit in the church today owes much of its flavor to the survival mentality of those early years and its being in a small community. “We always know that if we don’t do our fair share, it simply won’t get done, because there’s no one else here to do it.” We’re also told that Mr. and Mrs. Thomas regularly met the deficit of the church budget each year, if there was one – and there always was.

In 1900, several years after this fine beginning, Thomas died, and Mrs. Thomas and her daughters moved to St. Louis. Through a succession of interim clergy, the little congregation carried on valiantly, and faithful church members were being added to the registers. But the church seemed to be waiting for another saint to appear.

It came in the form of Father Robert James Belt, who came with his wife, Olga, in 1908 and stayed until 1923, the longest tenure of any priest at this church.

Father Belt’s contribution to All Saints’ is best stated by Mrs. Mantz: “The fifteen years during which Father and Mrs. Belt labored so earnestly with our people of Church School age were interesting and fruitful ones. To them we are indebted for our children’s spiritual training and deep love for the church.”

Since those “children” included Joe Aid, Jr., the late Charles Wood, Bob Neathery, Sr. and the late E.L. “Bob” Harlin, Mrs. Mantz spoke truer than she knew. Each of these faithful stewards of All Saints’ is or has been responsible for some important aspect of the church’s story.

Mrs. Belt wrote that Gran Stowers gave them an old square piano and “very often in the evenings, some of the young people dropped in, and we gathered the instrument and sang hymns or popular songs. Afterward we often made fudge or taffy. Sometimes we played games, but usually we wound up with discussions about religion, as several young men were interested in the subject, and Father Belt liked to seize the opportunity to instruct.” Grandsons of these men now live in West Plains, and still visit the rectory for the same reasons.

When the Belts left West Plains in 1923, the little congregation again was left to the mercies of visiting missionary priests until 1928 when Father Fairchild came.

In her history, Mrs. Mantz says, “During the 11 years Father Fairchild has been in charge, he and Mrs. Fairchild have labored sincerely and faithfully to keep up the high standards and to minister to the spiritual needs of the people. The church has been completely redecorated and many things added. Besides the missionary work in our section, he served the church at Mammoth Springs for several years and also a mission at Mtn. Grove. Through his efforts a beautiful little church has been erected and furnished at Mtn. Grove, and regular services are held there with a small but faithful group.”

The picture we have of Father Fairchild is a total contrast to that of Father Belt. Belt seemed to have been a quiet, studious man. Fairchild is remembered as a flamboyant extrovert who was involved in numerous community activities, including, the Masons and the Boy Scouts. His wife, by all accounts, was just as energetic in the sphere of guild work.

When the time came to celebrate the 50th anniversary in 1938, it was typical of Father Fairchild to do it in a big way, with a three-day celebration that included a visit by the bishop, a reading of church history, letters, telegrams – the whole works. The letters, filled with reminiscences and warm wishes, were placed in a Golden Anniversary Book and carefully annotated so that they may still be read and enjoyed.

Father Fairchild’s efforts might have come to naught, however, had he not a strong and flourishing flock to lead. Those “children” that Father Belt had so carefully instructed were now grown and had begun to take their places as the “younger set” in the congregation.

In addition, the faithful backbone was not only strong and sure, it evinced enough wisdom and human nature and humor to form the “All Saints’ Investment Club.” About the time of the Golden Jubilee in 1938, Hubert Wood, Joe Aid, Sr., Jerome Boyer and W.W. Mantz, all faithful members, met on the Square one day and started discussing church finances. They agreed that whenever the church got ahead by a few dollars, the priest – whoever it happened to be – would come along and find a way to spend it. “So they scraped together a little nest egg of $2,000 and deposited it in the West Plains Building & Loan Association without telling Father Fairchild about it, and kind of forgot the whole thing,” Bob Neathery recalled.

In 1957, Mont Widner, head of the building and loan company, mentioned the money to three of the four men’s sons and told them he was the only person who knew it belonged to the Episcopal Church. Would they please come over and transfer it into the church’s name before something happened to him and everyone would spend years in court trying to prove the money belonged to All Saints’?

The sons found the little “nest egg” had grown to $9,000 by then. Even more amusing, the wily old fellows had been right about the priest spending it. “The money was immediately snapped up and used to help pay for the new parish house,” Neathery laughed.

After the death of Father Fairchild in 1939 and the “low point” of the church attendance at the end of World War II, Father Warren Botkin had his work cut out for him. Very slowly – almost imperceptibly – the attendance figures began to improve and by the time Botkin left in 1949 and Father Robert Challinor came in 1950, the average Sunday attendance was in the high 20s.

But to understand what happened to Father Challinor’s bright beginnings, one really has to understand both Episcopal liturgy and Ozark culture. Normally the two live in harmony, but occasionally there are clashes. With more than a touch of truth, it has been joked that Episcopalians will tolerate almost any kind of theology, but don’t move the candles on the altar unless you’re spoiling for a fight. Such “appointments” are all in particular places for particular reasons, even in the humblest Episcopal church.

Father Challinor had been out of town when the church was set up for the funeral of a prominent townswoman and faithful communicant. When he returned he was horrified to find the flower arrangements had been draped all over the church, and even nailed to the reredos, a carved partition behind the altar. As one woman who was there explained it, “She (the deceased) was their sister, and the family members who had arranged the flowers were determined that everyone’s flowers were going to be seen.” Father Challinor, quite young, didn’t see it that way and several weeks later, or so the story goes. (No one ever seems to remember whether the flowers stayed up on the reredos during the funeral, however.)

Apparently Father Challinor harbored no permanent ill will over the incident, since he has returned to West Plains at least once and occasionally corresponds with members of the congregation.

Father Marcus M. Lucas served from 1951-1954, followed by Glen B. Coykendall from 1955-1956 and David L. Barclay from 1956-1958.

By the time of Barclay’s arrival, attendance had climbed into the low 30s. A whole new group of young people were beginning acolyte and choir training, some of whom represented the fourth or fifth consecutive generation of a family at All Saints’.

In June of 1957, there were two brief notations in the church register: “First marriage in 11 years,” and “Mrs. Page is waiting for labor pains.” Any church is bound to survive when there are marriages and babies being born. Two months later, the brief notation following Sunday school service says, “Broke all records on attendance at Sunday school.” By the time Father Barclay resigned, congregations were averaging in the 40s and sometimes in the 50s.

Father A.L. Burgreen was appointed to the mission in January of 1959, and for once there was no gap between priests. The years Father Burgreen was at All Saints’ appear to have been quiet ones, probably because he was a quiet, studious man, much on the order of Father Belt. To supplement his income, he taught at West Plains High School, where he is still remembered as a gentle man with a good sense of humor.

On February 23, 1964, All Saints’ celebrated its 75th anniversary. Bishop Edward R. Welles was present for the two-day celebration. Although the service seems to have lacked the flamboyance of the 1938 celebration, it more than made up for it in warmth and love. The spirit of it shines through dusty church files even now, almost 20 years later. Allene Chapin wrote another history of the Church for the occasion, and again letters were received from the past parishioners from all over the country, testifying to the spirit and influence of All Saints’ church.

The diocese also showed its appreciation for the outstanding work of its lay members. During the 1960s, Charles Wood, who had served devotedly as lay reader and warden of the church, Bob Neathery, Sr. and Joe Aid, Jr., were awarded Bishop’s Crosses, the highest award for a layman in the Episcopal Church.

Following Father Burgreen’s Retirement in 1965, Warren Sapp was appointed vicar of the church and remained here two years. For a year, in 1967, the church had no vicar, and again the struggle for survival was on, as the congregation strived to make its budget and carry on without a priest. That same year, the water pipes in the rectory burst and the plaster walls were ruined. The church badly needed painting and the steps were crumbling. Attendance was down and the outlook for All Saints’ again was grim.

When Father D.J. King arrived in 1968, his first sermon stressed how “unloved the church looked.” This was apparently an impetus to the people to improve both the exterior of the building and the interior lives of the congregation, for we begin to find references to more church activities and a general tightening of organization.

By September, 1970, the most urgent repairs were finished, and the congregation was, for the first time, talking about becoming self-supporting. In a burst of forward-looking optimism, the late Helen Frater led a successful fund drive to replace the old Hook & Hastings tracker organ with a Baldwin electronic organ.

When Father Robert Williams came to All Saints’ in 1971, the congregation was delighted to find he was a young man with a young family and young ideas. Also, they could show to him with pride their own accomplishments and improvements at All Saints’.

A significant contribution Father Williams made to All Saints’ was guiding the church though the paperwork and financial obligations necessary for obtaining parish status. To become a parish, the mission had to prove self-sufficiency for three consecutive years, which it did beginning in 1972.

Father Richard Daniel Brigham came in June 1974, and in November, 1975, at the diocesan convention in Springfield, All Saints’ became a full-fledged parish, after being a mission for 90 years.

In 1977, Mrs. Frater began to realize that the zeal with which the church had replaced the original organ was perhaps a mistake, and she began another campaign to restore it to its original state. The hunt for the organ’s innards, which had been taken out to make room for the Baldwin, took Father Brigham all the way to Kansas City in a borrowed pick-up truck to retrieve some of the pipes that had been stored in a basement there. The restoration of the organ is scheduled to be finished in the spring of 1981.

The years Father Brigham has been at the All Saints’ have been characterized by the joy of many marriages, many baptisms, and tears shed at the deaths of Workman, Charles Wood, Bob and Vesta Harlin, Kate Aid, Mary Sessen, Gail Harlin, Fritze Dixon, Clara Green, Bess Baker, Bob Pease and Thelma Meredith.

The years also have been characterized by the health and warmth of the Spirit at the All Saints’ as we live out our Christian commitment and lives as that “strange breed of cat” – Episcopalians in the Ozarks.

Did you know?

- That the All Saints’ Episcopal Church was established over an old graveyard?

- That due to the rarity of Episcopalians in the Ozarks at that time, a man referred to an Ozark Episcopalian, a “strange breed of cat?”